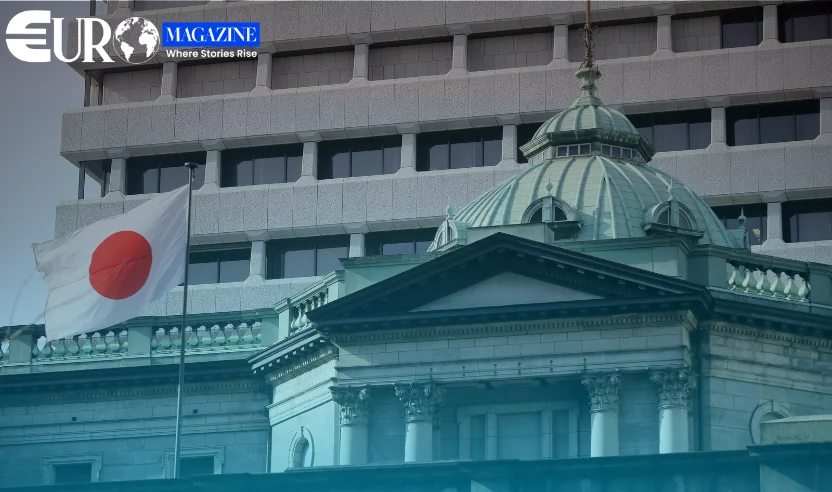

Tokyo - The Bank of Japan has raised interest rates to their highest level in three decades, marking a decisive shift away from ultra-loose monetary policy and reigniting concerns about rising global bond yields and capital flows.

At its December policy meeting, the BoJ lifted its key short-term interest rate by 25 basis points to 0.75%, the highest level since 1995. While the move itself was widely anticipated, the tone accompanying the decision was notably more hawkish than markets expected.

Governor Kazuo Ueda signalled that Japan’s era of exceptionally low interest rates is nearing its end, warning that delaying policy adjustments could require sharper rate hikes later. He also noted that previous increases have yet to meaningfully tighten financial conditions and that policy rates remain below estimates of neutral.

In its statement, the central bank said real interest rates are still “significantly negative” and that accommodative conditions will continue to support growth. However, it reaffirmed that further rate increases are likely if inflation and economic conditions evolve as projected.

The shift is closely watched beyond Japan because of the country’s outsized role in global bond markets. Japan remains the world’s largest net creditor, with overseas investments worth trillions of dollars. For years, ultra-low domestic yields pushed Japanese pension funds and insurers to invest heavily in foreign bonds, particularly U.S. Treasuries and European government debt.

As Japanese yields rise, that incentive weakens. Analysts warn this could lead to reduced foreign bond buying or even capital being repatriated back to Japan, putting upward pressure on global yields.

Early signs of that adjustment are already emerging. Yield gaps between Japanese government bonds and major global benchmarks have narrowed to multi-year lows, while long-dated European bond yields climbed sharply following the BoJ decision.

Economists say rising Japanese rates could also disrupt the yen carry trade, where investors borrow cheaply in yen to invest in higher-yielding assets abroad. As borrowing costs increase, that strategy becomes less attractive, raising the risk of broader deleveraging across global markets.

While further rate hikes are expected to be gradual, analysts agree the direction is clear. Japan is no longer the anchor of ultra-loose monetary policy it once was, and global markets may need to adjust accordingly.